“Do mask requirement mandates affect the growth of COVID cases in an area?”

I speculate the causality of this claim by analyzing Orange County and San Diego County as possible treatment and control. To do this, I’ll explore the COVID cases data from March 18th to July 18th and propose an identification strategy, endogeneity concerns, and possible ways to deal with them.

I’m from Orange County. Orange County has been in the news a lot lately. Unfortunately, it’s because of this. Orange County has had a lot of protests to reopen the county throughout lockdown. On June 9th, Orange County’s Chief Health Officer resigned after threats and criticism by anti-Mask protesters and Orange County Supervisors. Two days later, officials ended the mask requirement mandate. However, San Diego County, which is just south of Orange County, kept mask requirements.

Seeing that cases are now on the rise nationally and that my home has turned into the No-Mask movement’s epicenter, it seemed appropriate to look at whether there is an effect in mask requirement laws. We’ll first compare county cases over time and then outline an identification strategy that can validate a causal claim.

Why San Diego?: If we’re looking for any kind of causal effect in mask requirement laws and we’re using Orange County as our treatment, San Diego County is a good control. San Diego’s proximity to Orange County helps control for any regional/climate effects. They are similar in population size, differing only by 100,000 people. Both counties lean more conservative than other California industry centers (Los Angeles, San Francisco), and both economies rely on manufacturing and trade. Lastly, both counties experienced protests against the mask requirement order.

Most importantly, both counties began to open businesses and attractions at similar times, so we can control for growth from relaxing other COVID-related restrictions.

I’m going to use ggplot2 to graph the cases over time and cowplot to help with formatting.

The data comes from California Open Data Portal.

Subsetting the Dataset

The dataset does not contain data before March 17th except for total COVID cases. I subsetted the data frame into two separate data frames to get county specific data. I also created a column that counts the number of days since March 18th (beginning of the dataset). Then, I used rbind to merge county-specific datasets together. I think there is an easier way to subset a dataset by using select, but I wanted to create a number-of-days column for each county. I’m sure, though, that there’s a faster way to create an index column - I’ll update this article with cleaner code at some point.

oc.covid <- covid[ which(covid$county =='Orange'), ]

oc.covid$ind <- 1:nrow(oc.covid)

sd.covid <- covid[ which(covid$county == 'San Diego'),]

sd.covid$ind <- 1:nrow(sd.covid)

comp_covid <- rbind(oc.covid, sd.covid)

I also renamed the columns to follow my work.

colnames(comp_covid) <- c("county",

"total_count",

"deaths",

"daily_count",

"daily_deaths",

"date",

"ind")

Asymptomatic Period

I created two vertical lines on the 86th and 100th point of the x-axis in my graph.

Why? The x-axis denotes the number of days since March 18th. June 11th was the date when Orange County lifted the mask requirement. The two vertical lines highlight the maximum number of days for an infected person to be asymptomatic. These lines, which will look like a rectangle when graphed, start from the day officials lifted the mask mandate. In rare cases, symptoms can show up after 14 days, but the main idea behind highlighting the “Incubation Period” of the virus is that we can measure the effects from at least one day without the mask requirement.

rect <- data.frame(xmin=86, xmax=100,

ymin = -Inf, ymax = Inf)

Graphing Total Cases

The black vertical dashed line is the date when Orange County’s Health Officer resigned, and the transparent rectangle is the following 14-day Coronavirus Incubation period. During the Incubation Period, we can see that the total Orange County cases curve approaches the San Diego’s total case curve at an increasing rate, indicating that more people in Orange County are contracting COVID-19 than in San Diego County. After the 100th day, total cases in Orange County surpass total cases in San Diego County. Orange County’s daily case rate continues to increase from that day.

Some important information - Governer Newsom ordered Orange County to enforce the mask mandate on June 18th. Let’s add this to our graph.

ggplot(data=comp_covid, aes(x = ind, y = total_count)) +

geom_point(aes(color = factor(county))) +

geom_vline(xintercept=84, linetype="dashed", color = "black") +

geom_vline(xintercept=92, linetype="dashed", color = "green") +

geom_rect(data = rect,

aes(xmin = xmin,

xmax = xmax,

ymin = ymin,

ymax = ymax),

color="cornflowerblue",

alpha = 0.1,

inherit.aes = FALSE) +

ggtitle("Total New COVID Cases") +

theme(plot.title = element_text(lineheight=.8, face="bold"),

legend.title = element_text(lineheight=.8, face="bold")) +

guides(col=guide_legend("County")) +

labs(

x = "Number of Days since 3/18",

y = "Total Number of Cases")

Here’s an interesting point - COVID cases in Orange County grew at a similar rate to those of San Diego County until the end of the Incubation period. Afterwards, COVID cases in Orange County grew at a much faster rate than those of San Diego County.

Here’s an interesting point - COVID cases in Orange County grew at a similar rate to those of San Diego County until the end of the Incubation period. Afterwards, COVID cases in Orange County grew at a much faster rate than those of San Diego County.

A lagging indicator is economics jargon for a variable that becomes apparent only after a large, long-term shift occured. Infections, or the case rate, is a lagging indicator - the Incubation period accounts for time when infected individuals may be asymptomatic, or unaware that they are carrying the disease. Death occurs after infection, so naturally, death is also a lagging indicator. However, we don’t know how long it takes to die from COVID - some people die within days of contracting the virus, while some others die after several months.

With this in mind, let’s see how the death rate compares across counties.

ggplot(data=comp_covid, aes(x = ind,

y = deaths)) +

geom_point(aes(color = county)) +

geom_vline(xintercept=84,

linetype="dashed",

color = "black") +

geom_vline(xintercept=92, linetype="dashed", color = "green") +

geom_rect(data = rect,

aes(xmin = xmin,

xmax = xmax,

ymin = ymin,

ymax = ymax),

color="cornflowerblue",

alpha = 0.1,

inherit.aes = FALSE) +

ggtitle("Total COVID Deaths") +

theme(plot.title = element_text(lineheight=.8, face="bold"),

legend.title = element_text(lineheight=.8, face="bold")) +

guides(col=guide_legend("County")) +

labs(x = "Number of Days since 3/18",

y = "Total Deaths")

Again this is quite interesting, the death rate is higher in Orange County relative to San Diego County during the Incubation Period and afterwards. By the end of the of the graph, the number of deaths in Orange County match the number of deaths in San Diego County. This is the first time that there were more total deaths in Orange County than in San Diego County.

Again this is quite interesting, the death rate is higher in Orange County relative to San Diego County during the Incubation Period and afterwards. By the end of the of the graph, the number of deaths in Orange County match the number of deaths in San Diego County. This is the first time that there were more total deaths in Orange County than in San Diego County.

Another, arguably better way to visualize COVID cases over time and account for the 14 day incubation period is to plot cases by two week periods. These periods need to be, at the very least, divided before and after the highlighted Incubation period. We can then compare the COVID case rate by Incubation periods. This helps visualize the full impact of the virus in one day, by accounting for the maximum amount of time an infected person can stay asymptomatic. This also gives us a simple and powerful visualization of COVID cases over time. Simple and legible data visualization can go a long way.

library(dplyr)

comp_covid_adj <-

comp_covid %>%

mutate(period = ceiling((ind+2)/14))

comp_covid_adj$period <- as.factor(comp_covid_adj$period)

Creating a Two-Week period column

Through the dplyr package, I used the mutate function to divide the number of days column by 14 and round the result to the smallest integer that was greater than or equal to the result. To start an Incubation period on the date the mask requirement was lifted, I added two to the number of days.

Since the ninth two-week period is not done yet, we will filter out data that falls into the ninth two-week period. Adding incomplete data will not allow us to analyze the relationship properly.

comp_covid_adj$period_int <- as.numeric(comp_covid_adj$period)

covid_rn <- filter(comp_covid_adj, period_int < 9)

We added a numeric period column so that we could filter the dataset using inequalities. This will allow us to use a linear graph for further visualization.

For now, we’ll look at period as a factor. To visualize the number of new COVID cases per period, let’s create a grouped barplot.

ggplot(data=covid_rn,

aes(x = period,

y = total_count,

fill = county)) +

geom_bar(position="dodge",

alpha = 0.75,

stat="identity") +

geom_vline(xintercept=6,

linetype="dashed",

color = "black") +

geom_vline(xintercept=6.5,

linetype="dashed",

color = "green") +

geom_vline(xintercept=7,

linetype="dashed",

color = "black") +

ggtitle("Total New COVID Cases") +

theme(plot.title =

element_text(lineheight=.8, face="bold"),

legend.title =

element_text(lineheight=.8, face="bold"))+

guides(col=guide_legend("County")) +

labs(x = "Number of Two Week Periods since 3/18",

y = "Total Number of Cases")

The 6th period begins on the date mask requirements were lifted and the 7th period begins on the last day of the Incubation period.

The 6th period begins on the date mask requirements were lifted and the 7th period begins on the last day of the Incubation period.

The total new cases for the 7th period only accounts for people who contracted the virus before/by the end of the incubation period starting on June 11th. People who contracted the virus after the beginning of the 6th period, but did not develop symptoms before the end the 7th period, will not be recorded as COVID cases until the 8th period.

What’s great about this graph is that it gives us a better idea of the case rate in each county by smoothing out our data. Both barplots outline exponential growth, and we can clearly see that Orange County is growing at a much faster rate.

Specifically, this graph better highlights the dramatic increase in Orange County total cases from the 7th period to the 8th period. That is, Orange County gained more COVID cases after June 11th than did San Diego - the period after Orange County lifted its mask requirements.

Aside: Looking at the Daily Count

Let’s also look at the daily count of COVID cases among both counties and figure out if there’s a better way to visualize this.

This graph is messy and hard to look at, but we can glean from it that daily COVID cases increased after the highlighted Incubation Period.

This graph is messy and hard to look at, but we can glean from it that daily COVID cases increased after the highlighted Incubation Period.

Let’s look at Daily COVID cases over the beginning of Incubation periods, with the dashed lines denoting before and after the Incubation Period for June 11th. We’ll also use a grouped barplot to better organize the data points for visualization.

This graph shows that the daily count for COVID cases on the 6th period was similar between both counties. The Orange County daily count was higher than that of San Diego on the 7th period.

This graph shows that the daily count for COVID cases on the 6th period was similar between both counties. The Orange County daily count was higher than that of San Diego on the 7th period.

The first graph shows us how the amount of COVID cases changed after intervention.

In the second graph, we can see the difference in relative rate of cases between counties after intervention. This helps us understand the scale of the outbreak relative to San Diego.

We can see that, after six days without a mask mandate, Orange County had nearly three times the number of COVID cases as San Diego.

Revisiting the Total Cases Graph

Let’s see whether we can use this data to determine if there is a causal effect in mask requirement laws. To make a causal claim, we need an identification strategy. We’ll look at endogeneity concerns in this experiment and the feasibility of a Difference-in-Differences analysis.

What’s Difference-in-Differences? Our COVID dataset uses longitudinal data - that is, a dataset in which we can see multiple observations of an individual at different times. Longitudinal data allows us to see outcomes and treatment for multiple periods in an experiment. Observation terms therefore account for individual effects and time effects, since observations on one person can change over time.

To clarify, our treatment is no mask mandate and our control is keeping the mask mandate. Our treated group is Orange County and our control group is San Diego County.

In order to estimate causal effect using DID, several assumptions must hold, one of them being:

- Exchangeability - Data came from a randomized trial

We did not randomize anything in this study - COVID-19 happened and some states/counties reacted differently. Since we didn’t get this data from a randomized control trial (any study that randomly assigns individuals to treatment and control groups), we have to use the next best thing. That is, we have to find treatment and control groups that are as close as possible to each other. We also want to make sure that our treatment limits selection bias. Fortunately, our treatment doesn’t rely on whether individuals want to have no mask mandate or a mask mandate - Orange County and San Diego County officials chose to do different things during the pandemic, whether individuals want it or not.

Treatment could be correlated with unobserved individual-level shifters. We assume these shifters are constant within-individual across time and additively shift the outcome. While San Diego and Orange County have a lot in common, we still need to account for fixed effects such as the time the data was recorded.

In

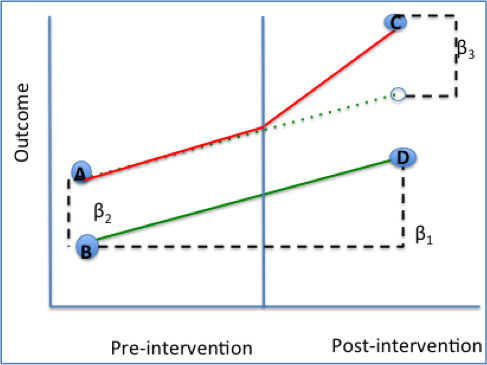

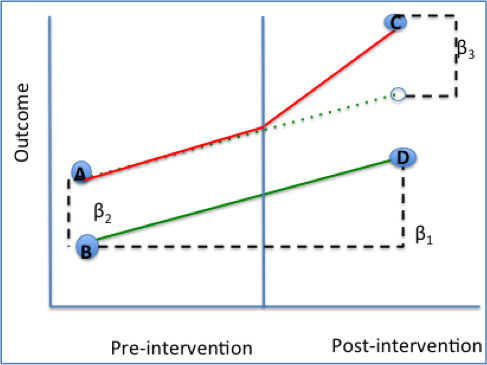

DID, we look at parallel trends between the treated and control group before and after intervention, assuming that each trend will stay parallel. Controlling for fixed effects and other covariates, we then measure the difference between the actual treatment line and the assumed parallel line. The best way for me to understand this is through the Potential Outcomes Framework. That is,

\[E(Y_{i2}(1) - Y_{i1}(0)|D_i = 1) - E(Y_{i2}(0)- Y_{i1}(0)|D_i = 1)\]

where

\(i\) is an index for individual changes and

\(1, 2\) are time periods. When

\(Y(1)\), the individual was treated. When

\(Y(0)|D = 1\), we are looking at the counterfactual - that is, the outcome where a treated indivudal was not treated. Since we can’t look at at two different outcomes for an individual, we need to assume what the outcome would’ve been. This is why we need parallel trends before intervention! This might be confusing, so here’s a graph I do not own of a perfect Difference-in-Differences Estimation.

The main idea is that the difference in the control group is what the difference in the treated group would have been, had it not been for treatment.

When writing out the general model, we denote

\(\beta_0\) as the baseline average

\(\beta_1\) as the time trend in the control group

\(\beta_2\) as the difference between groups pre-intervention

\(\beta_3\) as the difference in changes over time. That is, the difference in the treatment’s difference and the control’s difference over time.

and \[ Y_{it} = \beta_0 + \beta_1Time + \beta_2Intervention + \beta_3Time*Intervention \]

We can find the Difference-in-Differences through intertemporal variation between groups. In less jargon, we can look at the dependency between Time and Intervention to identify a causal effect.

Context

If we assume San Diego is a good reference for Orange County, and that trends the 84th day or the 86th day were nearly parallel, we could use Difference-In-Differences analysis to quantify the causal effect of lifting mask requirement after protests. We assume that, by lifting the mask requirement and undermining advice from top Health officials, the government encouraged a relaxed attitude towards combatting the virus and caused more infections.

Let’s look at the rest of the assumptions needed to do DID analysis.

Positivity - Any individual has a positive probability of receiving all values of the treatment variable.

Consistency - If \(Y_i\) is selected for treatment, We are observing the potential outcome of \(Y_i\) being treated.

SUTVA - The observation of one unit is unaffected by the assignment of treatments to other units.

Allocation of intervention was not determined by outcome

Let’s look at a linear graph of COVID cases over our two-week periods and evaluate whether this graph is suitable for DID.

Unfortunately, we’ve violated some of these assumptions. In fact, we didn’t have to look at this graph to find that out.

Let’s look at SUTVA. In context with our data, San Diego’s COVID cases should not depend on whether or not Orange County lifts the mask mandate - but it certainly could. Many people commute from Orange County to San Diego, and with businesses reopening/relaxed restrictions, Orange County folks may visit dense tourist centers, infecting many people. While San Diego may have mask mandates in place, there will still be more people with COVID in San Diego County than if San Diego County closed its border with Orange County - increasing the likelihood of San Diegans getting COVID.

Moreover, it seems that our data is not parallel for the entire dataset. Lines seem parallel between the 2nd and 4th Incubation period, but cross between the 4th and the 6th Incubation period.

More Problems?

The strategy explained here is restricted to linearity. We know that the trajectory of COVID cases follow a logistic curve. This is a big problem, but this can be avoided by looking only at the regression from the 7th period to the 8th period. This will not catch the full impact of the causal effect though. However, it may be notable to at least recognize the existence of the effect.

There are nonlinear DID methods, but I don’t know them. I will hopefully soon, but no, I don’t know them now.

Even though DID doesn’t seem feasible, graphs can still tell us a lot. What can we take away from these visualizations?

Orange County had had less cases than San Diego for 100 days. Now, there are more 6,471 COVID cases in Orange County than in San Diego (as of July 18th). COVID cases are increasing at a faster rate than ever.

As of Early-July, Orange County has a COVID case rate nearly three times higher than that of San Diego. Before then, Orange County and San Diego had had similar rates in COVID cases. This statistic accounts for the lag in infections caused by the time it takes for a virus to become symptomatic (The frequently-mentioned-in-this-article Incubation Period).

Here’s an interesting point - COVID cases in Orange County grew at a similar rate to those of San Diego County until the end of the Incubation period. Afterwards, COVID cases in Orange County grew at a much faster rate than those of San Diego County.

Here’s an interesting point - COVID cases in Orange County grew at a similar rate to those of San Diego County until the end of the Incubation period. Afterwards, COVID cases in Orange County grew at a much faster rate than those of San Diego County.

Again this is quite interesting, the death rate is higher in Orange County relative to San Diego County during the Incubation Period and afterwards. By the end of the of the graph, the number of deaths in Orange County match the number of deaths in San Diego County. This is the first time that there were more total deaths in Orange County than in San Diego County.

Again this is quite interesting, the death rate is higher in Orange County relative to San Diego County during the Incubation Period and afterwards. By the end of the of the graph, the number of deaths in Orange County match the number of deaths in San Diego County. This is the first time that there were more total deaths in Orange County than in San Diego County. The 6th period begins on the date mask requirements were lifted and the 7th period begins on the last day of the Incubation period.

The 6th period begins on the date mask requirements were lifted and the 7th period begins on the last day of the Incubation period. This graph is messy and hard to look at, but we can glean from it that daily COVID cases increased after the highlighted Incubation Period.

This graph is messy and hard to look at, but we can glean from it that daily COVID cases increased after the highlighted Incubation Period. This graph shows that the daily count for COVID cases on the 6th period was similar between both counties. The Orange County daily count was higher than that of San Diego on the 7th period.

This graph shows that the daily count for COVID cases on the 6th period was similar between both counties. The Orange County daily count was higher than that of San Diego on the 7th period.